China and Greenland: Why Beijing Cares, What It Wants, and Why It Keeps Getting Stuck

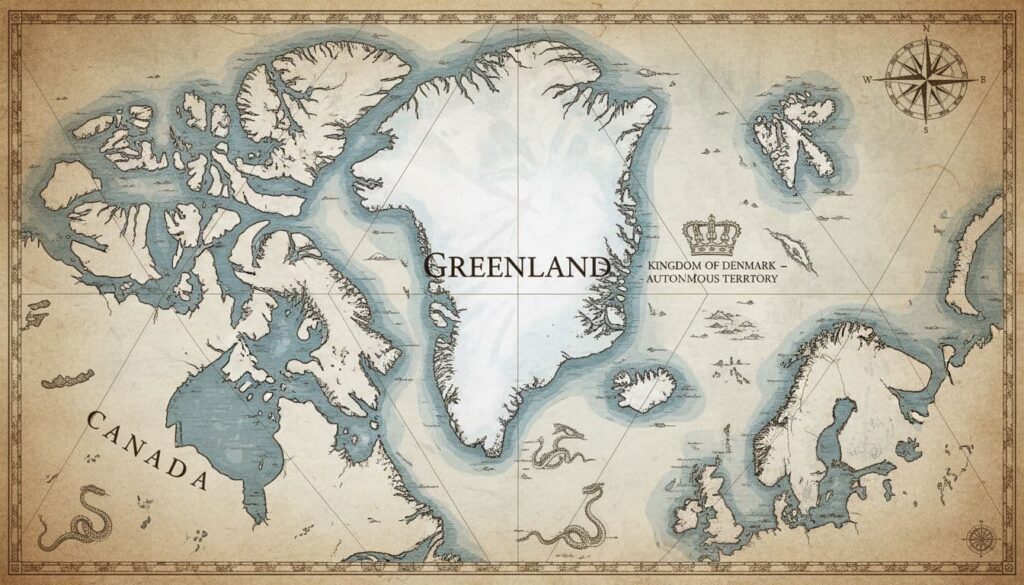

Picture a map in your mind. High above North America, past Canada’s Arctic islands, there’s a massive stretch of land covered in ice and rock. That’s Greenland, an autonomous territory in the Kingdom of Denmark, and it sits right where the Atlantic meets the Arctic.

Twenty years ago, Greenland was mostly a geography fact and a travel fantasy. Now it’s a headline. Warmer temperatures are changing the Arctic, demand for battery metals is climbing, and great powers are paying close attention to places they once ignored.

So where does China fit in? China’s interest in Greenland is less about buying the place (it isn’t for sale) and more about business and access: minerals, infrastructure, research ties, and a seat at the Arctic table. But many efforts have slowed, collapsed, or been redirected because Denmark and the United States treat parts of Greenland as sensitive for security reasons.

The United States’ interest in Greenland has always been rooted in hard security, the kind that shows up on maps and in military plans, not just in headlines. The United States has treated the island as a strategic shield for the North Atlantic and the Arctic, which is why it built and still operates major facilities there (today centered on Pituffik Space Base, formerly Thule). That focus isn’t new either, the US tried to buy Greenland in 1867 and again in 1946, and the 2019 purchase talk was flashy but it sat on top of a long pattern.

The U.S. president tied to the 2019 talk about buying Greenland was President Donald Trump. In August 2019, reports said he’d raised the idea inside his administration, and he later confirmed he was interested (he framed it as a strategic real estate style move, not a joke). Denmark and Greenland’s leaders pushed back fast, calling Greenland not for sale, since it’s an autonomous territory within the Kingdom of Denmark. Trump didn’t let it fade quietly either; after Denmark’s prime minister called the idea “absurd,” he canceled a planned state visit to Denmark, and the whole episode turned into one of those headline moments where foreign policy and blunt personal style collided in public.

In the first round of US “should we buy Greenland?” talk, the president was Andrew Johnson in 1867. His secretary of state, William H. Seward (the same guy behind the Alaska purchase), pushed the idea and even had reports prepared on buying Greenland (and Iceland) from Denmark, but Congress never moved it forward. Fast-forward to 1946 and the president was Harry S. Truman, with the State Department making a direct offer to Denmark to buy Greenland for $100 million (in gold), driven by post-World War II security worries and the island’s military value. Two different moments, two different presidents, same basic impulse: Greenland looked strategically useful, and Washington wanted it.

China’s interest looks different at first glance, more about access than alliance, with talk of research, trade routes, and investment. Beijing calls itself a “near-Arctic state,” and it’s pushed ideas like a “Polar Silk Road,” which is basically a plan to connect shipping, ports, and influence as ice retreats. In Greenland, that has shown up in interest around mining (including rare earths) and big infrastructure proposals, like airport projects that drew pushback from Denmark and concern from Washington.

If America’s approach feels like a security covenant (protect the route, watch the sky, keep rivals out), China’s feels like a patient business case (build ties, fund projects, gain options). But don’t miss the overlap: both countries care about the same realities, Arctic lanes, minerals, and what melting ice does to power and profit.

The difference is the method, the US leans on defense agreements and presence, China often starts with investment and science, then tests how far that access can go. And here’s the part that should make you sit up, Greenland isn’t just a piece of land in someone else’s story, it’s a self-governing society trying to weigh jobs, sovereignty, and security while two giants keep showing up with “opportunities” that come with strings.

What makes Greenland so valuable to China right now?

Greenland is valuable to China for the same reason it’s valuable to everyone else: it has resources the world wants, and it sits in a location that may matter more as the Arctic changes.

Think of it like a small town that suddenly finds itself on the route of a new highway. Even if the highway isn’t busy year-round yet, planners, investors, and governments start showing up early. They want options. They want relationships. They want to be there before rules and alliances harden.

For China, that “early positioning” solves a few practical problems.

First, China’s economy needs steady inputs. It builds EVs, electronics, power grids, and military hardware at enormous scale. Any country doing that worries about supply shocks, price spikes, and rivals cutting off access. Greenland offers the possibility of new sources, outside the usual suppliers.

Second, China wants influence in places where global rules are being written. The Arctic is one of those places. Being active in Greenland, even through normal commercial deals, helps China look like a serious Arctic stakeholder, not just a distant observer.

Third, relationships matter in the long run. A mining project today can lead to port upgrades tomorrow, research agreements next year, and shipping or logistics access later. Not ownership, but presence, and presence can shape outcomes.

If you want a detailed look at how resources and security concerns collide in Greenland, this analysis from CSIS is a solid starting point: Greenland rare earths and Arctic security.

Minerals that power phones, EVs, and wind turbines

“Rare earths” sounds like fantasy language, but it’s plain stuff that shows up in modern life. These are a group of metals used in magnets and components that help make:

- smartphone speakers and vibration motors

- EV motors

- wind turbine generators

- guidance systems and defense tech

Greenland has large mineral deposits that are still mostly in the ground. One of the best known is Kvanefjeld (also called Kuannersuit), which has been discussed for years as a major rare earth project.

Here’s the twist: China already dominates a lot of the rare earth supply chain, particularly processing and refining. Getting access to more upstream supply, even from a faraway place like Greenland, can help China keep influence over pricing, contracts, and downstream manufacturing.

Kvanefjeld also became politically toxic inside Greenland because the ore is mixed with uranium. In 2021, Greenland introduced a ban tied to uranium, which has effectively blocked that project from moving ahead at scale. That matters because it shows how quickly a “great deposit” can turn into a “stuck deposit.”

For a focused discussion of the China angle around Kvanefjeld and Shenghe Resources, see Shenghe and the Kvanefjeld Rare Earth Project.

A bigger Arctic footprint (science, shipping, and strategy)

People often talk about Arctic shipping like it’s a guaranteed shortcut from Asia to Europe. Reality is messier. Ice conditions vary, insurance is complicated, and ports and rescue capacity are limited. Still, shorter seasonal routes are getting more attention as climate patterns shift.

China calls itself a “near-Arctic state,” and it has pushed Arctic research and commercial engagement for years. Greenland fits that plan well because it offers practical things China can build ties around:

Research presence: science stations, climate work, and partnerships that look normal on paper, but also build long-term relationships.

Logistics and access: even limited port or airport involvement can matter in a region where transport options are scarce.

Political legitimacy: working with Greenlandic institutions helps China present itself as a partner in Arctic development, not an outsider trying to muscle in.

There’s also a simple reputational goal. When big Arctic decisions are discussed, China doesn’t want to be the country outside the room, staring through the glass.

What China has tried to do in Greenland (and what happened)

This part gets talked about in a dramatic way online, so let’s keep it grounded. China has shown real interest, and Chinese firms have pursued real projects. At the same time, Greenland is not a blank check for foreign plans, and Denmark and the United States take a close look at projects that touch critical infrastructure.

A pattern shows up again and again: China’s proposals often make financial sense on the surface, because Chinese state-linked firms can offer big financing or fast construction. But in Greenland, who builds can matter as much as what gets built.

As of January 2026 reporting, there haven’t been major new Chinese breakthroughs in Greenland. Several high-profile ideas were blocked, and Western governments have been nudging funding toward non-Chinese options, especially for minerals and infrastructure that could affect security.

A useful broader background on the push and pull between Greenland, Denmark, the US, and China is here: Wrestling in Greenland.

Big infrastructure bids like airports that raised red flags

In 2018, Greenland planned major airport construction and upgrades in Nuuk, Ilulissat, and Qaqortoq. A Chinese state-owned company, China Communications Construction Company (CCCC), was involved in the bidding discussions.

On paper, airports are normal infrastructure. In Greenland, they’re also lifelines. There are few roads between towns, so air links shape tourism, supply chains, and emergency response.

Denmark and the United States worried that a Chinese-built airport project could create long-term leverage over critical transport nodes, in a place tied to Arctic defense planning. The concern wasn’t that an airport is a military base, it’s that control over key infrastructure can create pressure points later.

Coverage at the time captured why the project set off alarms, especially given the US presence at Pituffik (Thule): risk concerns around a Chinese-built airport.

What happened next is the part that matters: Denmark stepped in with financing and took a stake in the airport company structure, which helped keep Chinese firms out of the most sensitive parts of the project. For a close look at how that controversy unfolded, see controversy over Greenland airports.

Mining partnerships aimed at rare earths

Mining is where China’s interest looks most straightforward. China wants minerals, Greenland has minerals. End of story, right?

Not quite.

China’s involvement has often been through minority stakes, partnerships, and processing agreements. Shenghe Resources is the name that comes up most, tied to Kvanefjeld through investment and agreements around processing and marketing if production ever begins.

But Greenland mining has a built-in reality check: even if a deposit is world-class, you still need roads, ports, power, skilled labor, housing, and a way to ship product in bad weather. Permitting takes years. Local politics matter. And global prices can change faster than a mine can be built.

There’s also competition. Recent reporting as of January 2026 points to Western-backed momentum around the Tanbreez rare earth project, which is majority owned by a US-linked company. That kind of shift matters because it signals a broader goal in Washington and Copenhagen: expand mineral supply while reducing China’s role in strategic processing chains.

If you want a current policy-oriented take on why Greenland’s minerals take patience (and why governments keep getting involved), this Atlantic Council piece lays it out clearly: Greenland’s critical minerals require patient statecraft.

What China likely wants next, and what could slow it down

It helps to stop thinking in extremes. China doesn’t need to “own” Greenland to gain something from it. Influence can come from contracts, financing, and being the buyer that shows up when others hesitate.

At the same time, Greenland isn’t a passive prize. Greenlandic leaders have their own goals: more jobs, more private-sector growth, and less dependence on Danish subsidies. But they also have to answer to voters who care about land, fishing, and environmental risk.

So the future is likely to look like a tug-of-war between opportunity and fear, with Greenland trying to keep control, Denmark trying to manage security and sovereignty, and the United States trying to prevent strategic footholds near Arctic defense assets.

Here’s a simple way to see the tension:

| What China wants in Greenland | What can block it |

|---|---|

| Long-term mineral access | Local environmental rules and politics |

| Stakes in projects (not full control) | Denmark’s oversight and funding options |

| Infrastructure roles (ports, power, telecom) | US and Danish security screening |

| Research ties and logistics presence | Public skepticism and reputational risk |

| Offtake deals (future purchase contracts) | Harsh economics and slow timelines |

China’s practical wish list: deals, access, and long-term influence

If you strip away the headlines, China’s “wish list” in Greenland is pretty recognizable:

Minority stakes in mining companies: less political blowback than full takeovers, but still influence.

Offtake agreements: contracts to buy output in advance. This can be powerful because it shapes where minerals flow, even if China doesn’t run the mine.

Financing for enabling infrastructure: ports, power generation, roads, and housing. Mines don’t work without the boring stuff.

Telecom and communications projects: not always public, often controversial. In Arctic regions, connectivity is strategic as well as economic.

Research cooperation: science agreements build relationships and allow a long-term presence that looks normal and peaceful, which is often the point.

The key idea is “control without owning.” If you finance the port, pre-buy the product, and process the material, you’ve gained a lot, even if Greenlandic authorities remain the legal decision-makers.

The hard realities: security pushback, local choices, and harsh economics

There are three big brakes on China’s plans in Greenland.

First, security scrutiny is real and it’s getting sharper. Denmark and the US don’t treat Greenland like a normal small economy where any investor is welcome. They look at airports, ports, satellite links, and dual-use infrastructure through a defense lens, because that’s how Arctic planning works.

Second, Greenland’s internal politics can stop projects cold. Kvanefjeld is the clearest example. The uranium issue isn’t a technical footnote, it’s a community-level fear about pollution, waste, and long-term damage. For many residents, the question isn’t “How much money can we make?” It’s “What are we risking, and who pays if something goes wrong?”

Third, Arctic economics are brutal. Everything costs more: construction, labor, shipping, insurance, energy. A mine that looks profitable in a spreadsheet can look shaky once you price in winter storms, limited daylight, and a small local workforce that can’t be stretched forever.

This is why Greenland sometimes signals a preference for Western partners, but still keeps the door cracked for China. If Western governments say “no” to Chinese involvement, they often have to answer the follow-up question: “Okay, then who funds it?”

Conclusion: Greenland isn’t for sale, but access is always on the table

China’s focus on Greenland boils down to two linked aims: locking in long-term access to key minerals and building a steady Arctic foothold through ordinary-looking business deals and research partnerships. Many of China’s most visible attempts, like airport involvement and rare earth-linked partnerships, have run into heavy scrutiny, local resistance, or direct counter-funding from Denmark and the United States.

What should you watch next? Keep an eye on whether Western investment actually shows up at scale, whether new offtake deals quietly shape where Greenland’s minerals go, and whether the next big infrastructure proposal triggers another round of blocking and replacement funding. In the Arctic, the loudest battles often happen in the fine print.

Return to homepage.