Muslim Brotherhood Explained: History, U.S. Debates, Trump, Obama, and What Might Come Next

The phrase Muslim Brotherhood gets thrown around a lot in American news, talk radio, and social media. Sometimes it is used as a catch‑all label for almost any Islamist group. Sometimes it is tied to big claims about U.S. politics, Donald Trump, or Barack Obama.

That mix of fear, rumor, and real history can get confusing fast.

This article walks through who the Muslim Brotherhood is, where it started, how it recruits followers, what groups are linked to it, and what its stated goals are. It also looks at what Donald Trump and his allies have said, why some U.S. officials want to label the Muslim Brotherhood a terrorist group, and how Barack Obama’s administration dealt with Brotherhood leaders during the Arab Spring.

The topic is controversial, so the goal here is simple: clear, sourced information. You will also see graphs, tables, and images that could help turn this complex story into something you can see, not just read.

For solid background while you read, you can compare what follows with summary articles from Encyclopedia Britannica and the Council on Foreign Relations, both of which track the history of the Muslim Brotherhood in depth.

What Does “Muslim” Mean and Who Are the Muslim Brotherhood?

Before talking about politics, it helps to separate two big ideas: Muslims in general and the Muslim Brotherhood as a specific movement.

Simple definition of a Muslim and basic Islamic beliefs

At the most basic level, a Muslim is a person who follows Islam.

A Muslim believes:

- There is one God, called Allah in Arabic.

- Muhammad is God’s final prophet.

- The Qur’an is God’s final message to humanity.

Most Muslims also try to live by the “five pillars” of Islam: declaration of faith, daily prayer, charity, fasting in Ramadan, and pilgrimage to Mecca if they are able.

Here is the key point for this whole article:

Most Muslims have nothing to do with the Muslim Brotherhood, or with any organized Islamist or extremist group. Calling all Muslims “Muslim Brotherhood” would be like calling all Christians “the Vatican” or “the religious right.” It just is not accurate. But, if you want to learn the true history of Islam itself and how it stacks up against Christianity, check out Stir Up America’s article on that below:

Clear definition of the Muslim Brotherhood as a movement

The Muslim Brotherhood is a specific religious, social, and political movement that began in Egypt in 1928. It is not a branch of Islam. It is an organization that claims to act in the name of Islam.

According to sources like Wikipedia’s history summary and Britannica, the group:

- Started in Egypt as a small Islamic revival movement

- Grew into a wide network that mixed preaching, charity, and politics

- Is often called an Islamist group, meaning it wants Islamic ideas to guide government and law

Different branches of the Muslim Brotherhood can look very different from each other:

- Some run charities, clinics, and schools.

- Some run for office as political parties.

- Some have been accused of inspiring or supporting violence.

This mix is one reason governments and experts argue so much about how to label the Muslim Brotherhood.

Origins of the Muslim Brotherhood: Where, When, and Why It Started

To understand why the Muslim Brotherhood matters today, we have to look back to Egypt almost 100 years ago.

Founding in Egypt in 1928 and the role of Hasan al‑Banna

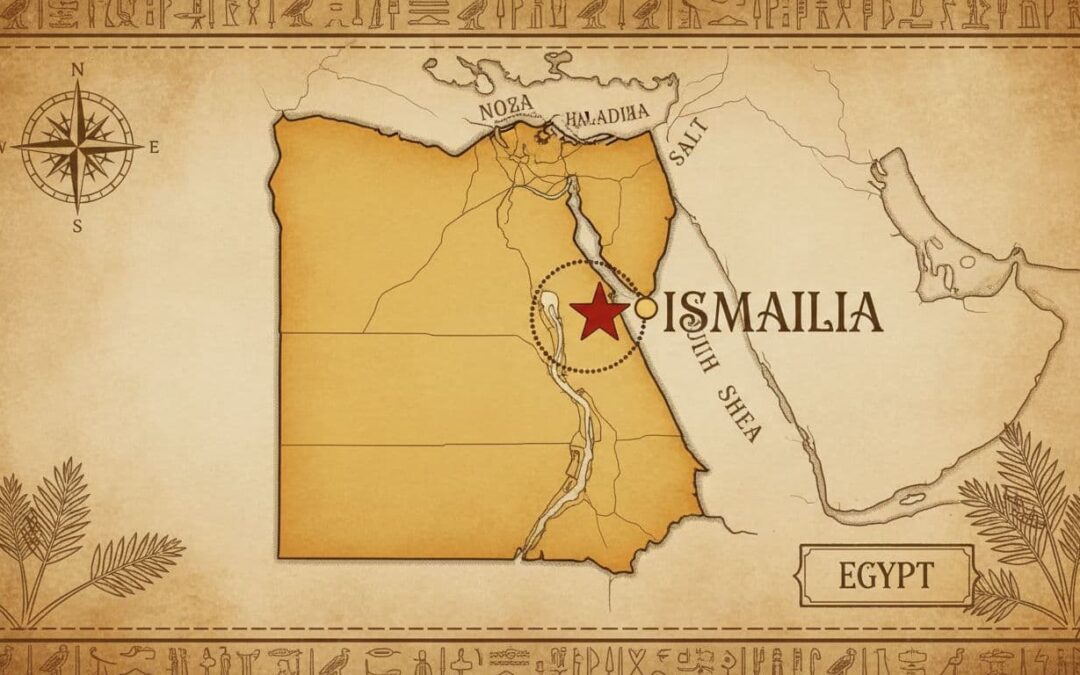

The Muslim Brotherhood was founded in 1928 in the Suez Canal town of Ismailia, Egypt, by a young schoolteacher named Hasan al‑Banna.

According to the Federation of American Scientists profile, Al‑Banna was:

- Deeply religious

- Upset by what he saw as moral decline in Egyptian society

- Angry about British influence and control over parts of Egypt

He believed Islam should guide every part of life, including politics, education, and law. He started the group with a handful of workers, but by the late 1930s and 1940s it had spread across Egypt and then beyond. As CFR’s backgrounder on Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood notes, it became one of the most influential Islamist movements in the world.

Political and social conditions in Egypt that helped the group grow

The Muslim Brotherhood did not grow in a vacuum. Several pressures in Egypt helped it expand:

- British colonial influence felt humiliating to many Egyptians.

- Poverty and inequality were widespread.

- Some elites looked to Europe, and many religious Egyptians felt their culture was being pushed aside.

The Muslim Brotherhood stepped into that gap. It built:

- Schools

- Clinics

- Charity organizations

People who felt ignored by the state suddenly had someone offering help. That mix of social services, religious message, and Egyptian nationalism helped the Muslim Brotherhood gain a strong base among the poor and lower middle class, as described in historical overviews like this Beirut feature on Hasan al‑Banna.

How the Muslim Brotherhood Recruits and Spreads Its Ideas

The Muslim Brotherhood does not recruit like a modern brand with TV ads. It works more like a dense web of relationships, charities, and religious teaching.

Recruitment methods: mosques, schools, charities, and social networks

Research on the art of recruitment in the Brotherhood, such as studies summarized in academic work hosted by Oxford University Press, describes a familiar pattern. People are often drawn in through:

- Mosques, where preachers talk about returning to Islamic values and fighting corruption

- Youth groups and student circles, where young people study religious texts and talk about politics

- Charity projects, where volunteers hand out food, teach classes, or run clinics

- Family and friends, who invite someone to a meeting, a lesson, or a small study circle

A British government review of the group’s activity in the UK, known as the Muslim Brotherhood Review, also points to student groups and charities as key hubs.

In some countries, national branches of the Muslim Brotherhood are legal political parties. In those places they also recruit like any other party, with campaigns and policy programs. In other countries, the Brotherhood is banned, so recruitment is underground and much harder to track.

Use of media, the internet, and global networks to share the message

From early on, the Muslim Brotherhood used whatever media tools were available:

- Newspapers and pamphlets in the mid‑20th century

- Satellite TV in the 1990s

- Websites and social media in the 2000s and 2010s

Reports on the Muslim Brotherhood in Europe, such as a study hosted by the European Conservatives and Reformists Group, argue that Brotherhood‑inspired networks helped set up student groups, cultural centers, and charities in several Western countries. Many of those groups deny direct control from Cairo, but the general pattern is clear: ideas spread along personal, religious, and family networks, not just formal party structures.

Goals, Purpose, and Global Affiliates of the Muslim Brotherhood

So what does the Muslim Brotherhood say it wants, and where has it built real power?

Stated purpose and long term goals of the Muslim Brotherhood

From its founding documents, the Muslim Brotherhood has said its purpose is to:

- Make individuals more pious and committed to Islam

- Build an Islamic society that reflects those values

- Push back against foreign rule and “corrupt” local elites

- Gradually create governments that base their laws on sharia (Islamic law)

Historians note that the Brotherhood’s motto includes lines about jihad and death “in the path of God.” Leaders have sometimes said they support peaceful political work, especially when they run in elections. Critics point to:

- Episodes of violence by members or splinter groups

- Support for armed resistance in places like Israel

Government hearings, like the U.S. House session titled “The Muslim Brotherhood’s Global Threat”, collect many of these accusations and try to link the Muslim Brotherhood to specific militant acts. Supporters argue that the group has mostly shifted to ballots, not bullets, in recent decades. Both sides use selected parts of the record.

Key branches and affiliates in the Middle East and North Africa

The Muslim Brotherhood is often described as a global network, but it does not run like a single company. National branches share ideology and history, yet they respond to local politics.

Commonly discussed branches and affiliates include:

| Country / Territory | Group or Party | Status (approximate, always changing) |

|---|---|---|

| Egypt | Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood | Banned, leaders jailed since 2013 coup |

| Jordan | Islamic Action Front | Legal political party |

| Gaza Strip | Hamas | U.S. and EU designated terrorist organization |

| Syria | Syrian Muslim Brotherhood | Opposed Assad, hunted by regime |

| Tunisia | Ennahda Movement | Legal party, disputes over Brotherhood label |

| Sudan | Islamist movements linked to Brotherhood | Influence has risen and fallen with coups |

Hamas is widely described as an offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood. The U.S. and EU list Hamas as a terrorist organization, which is a major reason some American politicians push for terror labels on the wider Muslim Brotherhood.

Scholars still debate how closely parties like Tunisia’s Ennahda should be tied to the Muslim Brotherhood label. Some leaders call themselves “Muslim democrats,” like Christian Democrats in Europe, and say they have moved away from older Brotherhood models.

Debates about Muslim Brotherhood linked organizations in Europe and the United States

In Europe and North America, the picture gets blurred.

Studies like the UK’s official Muslim Brotherhood Review and independent reports on the Muslim Brotherhood in the UK argue that:

- Some community groups and charities are inspired by Muslim Brotherhood ideas

- Some leaders once held roles in Brotherhood linked movements abroad

Many Western Muslim groups reject the label and say they focus on civil rights, anti‑discrimination work, and community services, not on building an Islamic state.

In the United States:

- The Muslim Brotherhood is not registered as a party.

- It is not listed as a Foreign Terrorist Organization as of the latest public data.

Claims about “Muslim Brotherhood fronts” often appear in opinion pieces and activist reports. Independent verification is hard, and affiliation is a contested topic.

Muslim Brotherhood, the United States, and Terrorist Designation Debates

Now we reach the hot part of the conversation in American politics: should the Muslim Brotherhood be labeled a terrorist organization?

What Donald Trump has said about the Muslim Brotherhood

During and after his presidency, Donald Trump and several of his allies spoke openly about labeling the Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist group.

Reporting and analysis from places like the Washington Institute for Near East Policy describe Trump officials exploring an official designation. Members of Congress held hearings, including the one titled “The Muslim Brotherhood’s Global Threat”, to build a public case.

In later political seasons, some Republican figures publicly backed Trump’s talk about designation, as in statements highlighted by party sites and press releases that support naming the Muslim Brotherhood a terrorist group.

Despite this pressure, U.S. officials did not complete a full global terrorist designation for the entire network.

Why some U.S. officials want to label the Muslim Brotherhood a terrorist group

Supporters of a U.S. terrorist label make several main arguments:

- Links to Hamas and other militant groups that are already on U.S. terror lists

- Past violence by some Brotherhood members and splinter groups

- Court cases in the U.S. and Europe where prosecutors mentioned Brotherhood connections

- The claim that the Muslim Brotherhood uses charity and politics as a cover for long‑term radical goals

These arguments show up in congressional testimony and policy debates. At the same time, analysts, including some at the Washington Institute, warn that labeling the entire Muslim Brotherhood as terrorist could be too broad and legally fragile, since many branches operate as normal political parties.

U.S. government reviews under different administrations have reportedly found mixed evidence, leading them to target specific groups like Hamas rather than the whole global Muslim Brotherhood.

What might happen if the Muslim Brotherhood is formally labeled a terrorist organization in the U.S.

So what if a future administration or Congress did succeed in labeling the Muslim Brotherhood a terrorist organization?

Based on how U.S. law works for other groups, likely effects would include:

- Asset freezes for any bank accounts tied to designated parts of the Muslim Brotherhood

- Travel bans and visa blocks for known leaders or major donors

- Criminal penalties for “material support,” which can include money, training, or services

For American groups accused of being affiliates, even if they deny it, there could be:

- More FBI and Treasury investigations

- Donors afraid to give money, even for basic charity work

- Pressure from media and politicians to “prove” they are not part of the Muslim Brotherhood

Security advocates say this kind of label could help choke off support for radical networks. Civil rights groups warn it could hit peaceful Muslim charities and mosques, damage religious freedom, and fuel fear of ordinary Muslims.

Those are predictions, not facts yet, but they come from experts who study terrorism law and civil liberties.

Barack Obama, the Muslim Brotherhood, and White House Engagement

Barack Obama’s name often shows up in debates about the Muslim Brotherhood. Some people say he supported the group. Others say he simply dealt with whoever held power in the Middle East.

The truth lies in a messy middle.

U.S. policy toward the Muslim Brotherhood during the Obama years

When the Arab Spring began in 2010 and 2011, long‑time leaders in countries like Egypt and Tunisia fell. In Egypt, elections brought the Freedom and Justice Party, linked to the Muslim Brotherhood, to power. Mohamed Morsi, a Brotherhood figure, became president.

The Obama administration:

- Did not name the Muslim Brotherhood a terrorist organization.

- Tried to work with the elected Egyptian government while also keeping ties with the Egyptian military.

Writers who are critical of Obama’s approach, including an article hosted by Orient XXI on Obama and Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, argue that the administration placed too much hope in Brotherhood leaders. Others see it as practical diplomacy, engaging whoever won a fair vote.

In 2013, the Egyptian military removed Morsi and banned the Muslim Brotherhood again. The U.S. did not declare the overthrow a coup in legal terms, which let it keep funding the Egyptian army.

Did Barack Obama or his team invite Muslim Brotherhood linked figures to the White House?

This question sparks a lot of online arguments, so it helps to separate what is documented from what is rumor.

Some key points:

- According to research on U.S. outreach to Islamists, Obama’s 2009 Cairo speech included Muslim Brotherhood leaders in the audience as “special guests,” which angered then‑president Hosni Mubarak. The episode is discussed in an academic article on U.S. partnership with the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood available through PMC.

- After Mohamed Morsi won Egypt’s presidency, Obama invited him to visit the United States, as reported at the time by outlets like Reuters and The Guardian.

Beyond that, there were broader Muslim community meetings at the White House that included American Muslim leaders. Some critics claimed certain attendees had Muslim Brotherhood ties, but hard proof of full organizational control from Cairo is thin and often disputed.

The Obama administration defended its outreach as:

- Part of engagement with Muslim communities

- A way to understand views on foreign policy, civil rights, and counterterrorism

- Standard diplomacy with elected leaders in the Middle East, whether secular or Islamist

Think tanks like the Washington Institute even published pieces arguing that the administration should not meet Muslim Brotherhood leaders in Washington, which shows how divided expert opinion was.

How engagement and the Arab Spring changed the Muslim Brotherhood’s power and reach

The Arab Spring cracked open political systems that had been frozen for decades. For the Muslim Brotherhood, this meant:

- Legal recognition in some countries

- A chance to run openly in elections

- Big wins, especially in Egypt and Tunisia, at least for a short time

Public opinion polls from groups like the Pew Research Center during that period showed meaningful, though not majority, support for Brotherhood linked parties in some countries. Many voters saw them as honest, religious, and not tied to old corrupt elites.

Once Egypt’s military removed Morsi and cracked down, the picture flipped:

- Thousands of members and supporters were arrested.

- The Muslim Brotherhood was labeled a terrorist group by the Egyptian state.

- The movement in Egypt was pushed underground again.

In other countries, such as Tunisia, Brotherhood inspired parties tried to moderate their image, work in coalitions, and drop some of the harsher rhetoric. Their influence rose and fell with shifting elections and security crises.

Obama’s decision to work with elected Islamist governments gave critics an easy target. Yet when those same governments fell or were repressed, the U.S. mostly kept working with the new rulers too. That suggests continuity in state interests, not a deep personal alliance with the Muslim Brotherhood.

Statistics, Visuals, and What the Numbers Really Show

Counting members of a partly underground, global movement is like counting shadows. You get estimates, not exact totals.

Membership, election results, and public support over time

Researchers often use three types of numbers to study the Muslim Brotherhood:

- Membership or supporter estimates

- In Egypt, estimates have ranged from hundreds of thousands of members to several million sympathizers at different points from the 1950s to the 2010s.

- Because of repression, numbers are always uncertain.

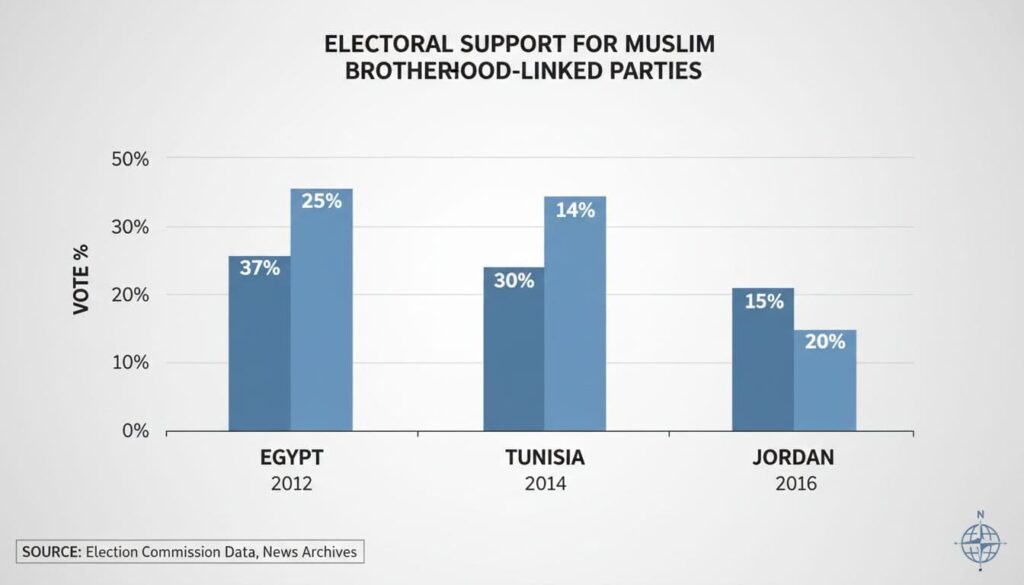

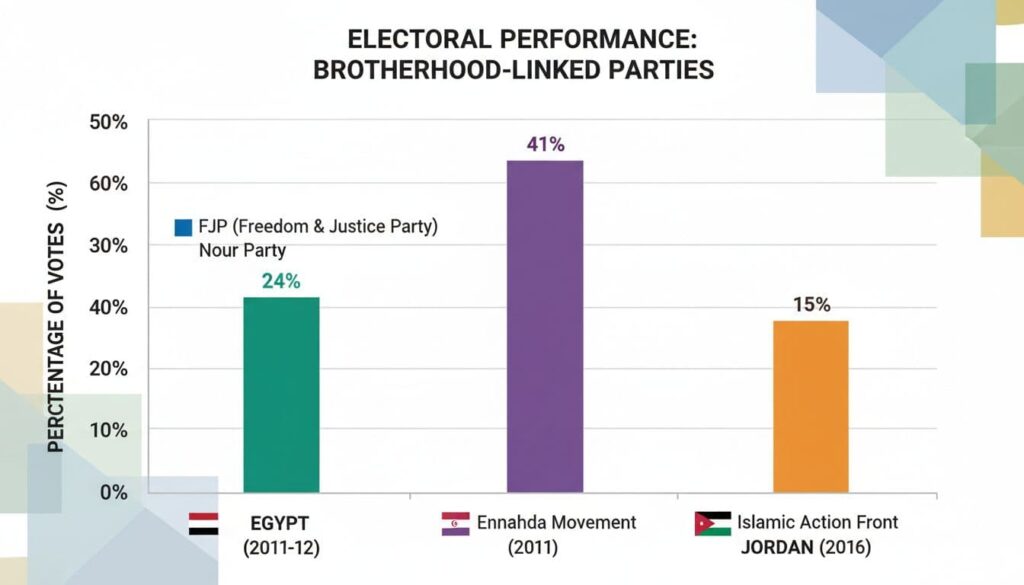

- Election results

- In Egypt’s 2011–2012 parliamentary elections, Brotherhood linked parties won close to half the seats in some chambers.

- In Tunisia, Ennahda won a plurality but not a majority in early post‑revolution votes.

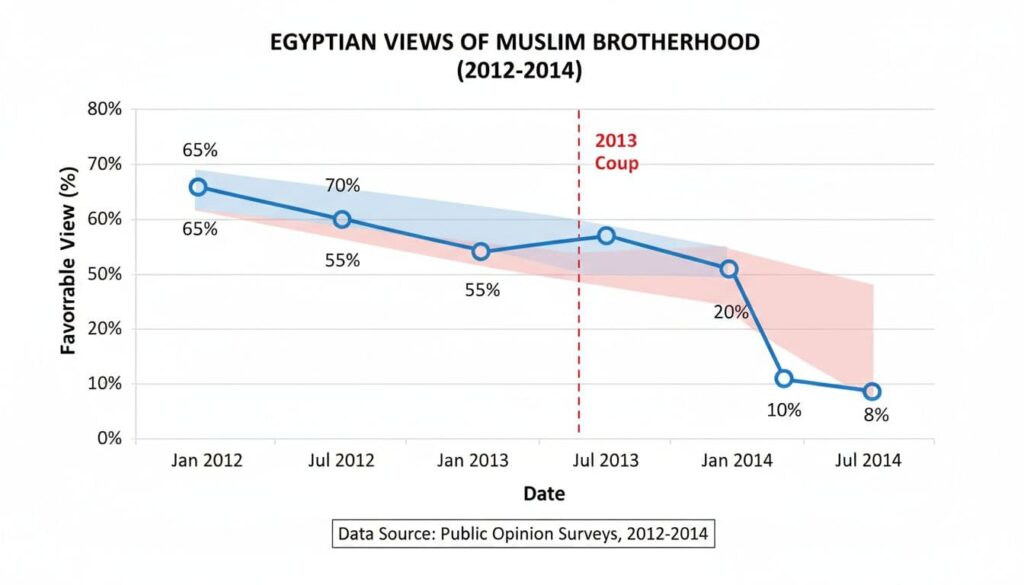

- Public opinion polls

- Pew and local pollsters have measured favorable or unfavorable views of the Muslim Brotherhood in countries like Egypt, Jordan, and Tunisia.

- Support often spikes after a revolution, then falls when parties struggle to govern.

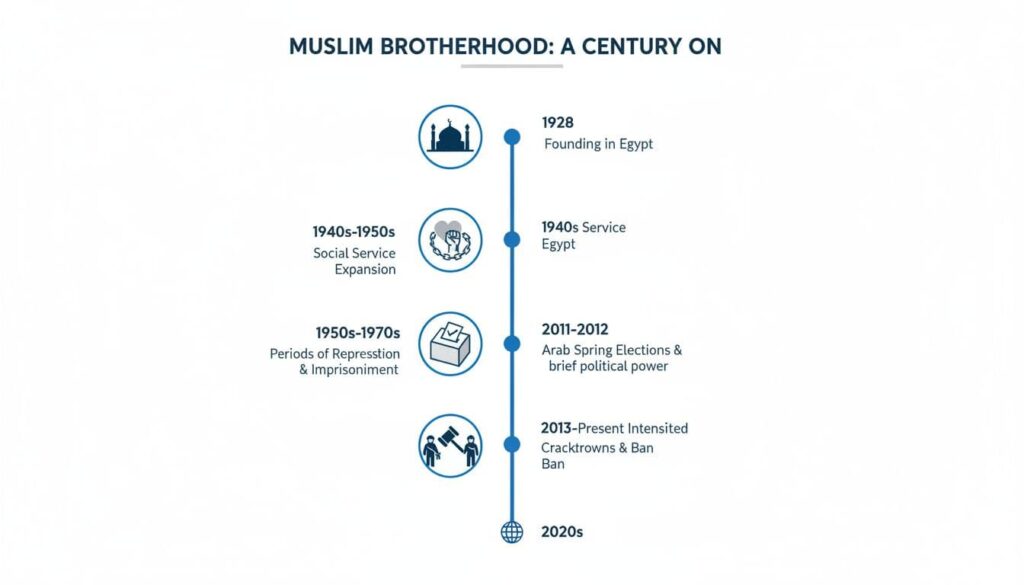

Here are some visuals, as accurate as possible:

- A bar chart comparing election results of Brotherhood linked parties in Egypt, Tunisia, and Jordan.

- A line graph showing how favorable views of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt shifted before and after the 2013 coup.

Those graphs do not give exact membership, but they show the rise and fall of influence over time.

Graphs and Tables to Make the Data Easy to See

- Timeline graphic of key events

- Bar chart of election results

How to Read Claims About the Muslim Brotherhood in American Media

You will see the phrase “Muslim Brotherhood” used for everything from serious policy debate to wild conspiracy threads. That means you need a filter.

Checking sources, bias, and context when you see the Muslim Brotherhood in the news

Some simple checks help:

- Who is talking? Is it a news reporter, a politician, a think tank, a random influencer?

- Do they cite evidence? Look for links to court documents, official reports, or research from places like Britannica or the Council on Foreign Relations.

- Is there only one side? If a piece only quotes people who hate or love the Muslim Brotherhood, it is probably opinion.

- Are facts mixed with emotion? Heavy use of labels like “traitor,” “enemy within,” or “secret Islamist” is a warning sign.

For example, you can compare a heated speech or op‑ed with more technical background from CFR or Britannica to see what lines up and what does not.

Why it matters for Muslims and non‑Muslims in America

How Americans talk about the Muslim Brotherhood affects more than one movement in Egypt. It can shape how neighbors look at the mosque down the street.

If every mosque or charity is treated as a secret arm of the Muslim Brotherhood, even without clear evidence, then:

- Ordinary Muslims can face unfair suspicion.

- Peaceful activism, charity work, and civil rights organizing can be smeared.

- Real threats of violent extremism can be harder to spot in the noise.

At the same time, ignoring real problems, such as proven ties between some groups and violence, does not help either.

The goal should be careful language that separates:

- A global organization called the Muslim Brotherhood

- Other Islamist or militant groups

- The billions of Muslims who are not part of any of these networks

That kind of clarity protects both security and fairness.

Conclusion

The Muslim Brotherhood is not a shadowy code word for all Muslims. It is a nearly century‑old movement that began with a young teacher in Egypt, grew through social work and preaching, and later stepped into electoral politics and, at times, confrontation.

You have seen how it recruits through mosques, charities, and personal networks, how national branches across the Middle East and North Africa have followed different paths, and how their power surged and then collapsed in places like Egypt after the Arab Spring. In the United States, you have also seen why Donald Trump and some allies have pushed to label the group a terrorist organization, and why other experts warn that such a move could sweep in too many people and organizations.

Barack Obama’s record shows cautious engagement with elected Islamist leaders and community figures, followed by continued ties with new rulers when those leaders fell. That is messy, but it looks more like shifting diplomacy than a secret alliance.

If you take anything away, let it be this: complex global movements require good information, not slogans. Keep reading primary sources, look at the suggested graphs and tables, compare different news outlets, and ask hard questions before you accept big claims about the Muslim Brotherhood or about Muslims in America.

Many Muslims love God, they just do not understand God’s name is Yahweh (Father Son & Holy Spirit), not Allah, this is where the Great Commission from Jesus comes into play. Many Muslims are afraid to leave their religion, but Jesus will pull all of His people out of any religion they do not belong to in heart.

Return to homepage.